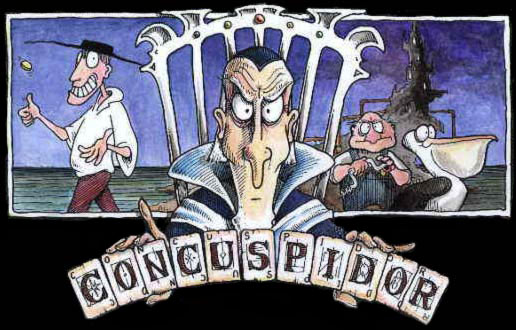

By now (July 2015), the Concuspidor can start celebrating having completed his second decade on the web. More accurately, at the very end of June 1995 the first instalment of the story The Concuspidor & the Grand Wizard of Many Things was published online. The story progressed in weekly instalments from that point on until its conclusion six months later, just before Christmas 1995.

The Concuspidor & the Grand Wizard of Many Things complete with authentic 1990s-style JPEG compression artefacts

It was the first story to be told in this particular way, and I believe the first web comic in the UK to be produced and delivered solely online. At the time, it was deliberately exploiting image caching (because download speeds were so slow as to be the limiting factor back then). Your browser downloaded the illustration but then reused it because, as you clicked on the characters in the screen, subsequent requests were just pulling down comparatively small HTML pages containing the text. Nerdy historians can read more about this over on the Concuspidor history page, and there’s more information in the Concuspidor FAQ.

“the higher above the world you are, the freer your shadow is to wander”

— from the Box of Answers (in Phlegm)

The Concuspidor got a little attention at the time, including some positive reviews in the computer (offline) press. He’s been online ever since, together with his put-upon sidekick Cog, and their unexplained companion Phlegm the Pelican (who is integral to both the plot and the Answers-to-Everything reveal gag later in the story). In 2012 I added JavaScript to deliver the story in popups because it seems to make it easier to read. But other than that it remains fundamentally unchanged, a snapshot of a project delivered for the early web. As it happens, the broad-hatted buffoon served Beholder well because his presence online led to creation of the flagship puzzle Planetarium, which continues to delight and absorb a select band of patient readers to this day.

“castles built in air must address the problem of waste disposal responsibly”

— from the Box of Answers (in Phlegm)

The Concuspidor’s story contains many explicit elements of computer culture, which made sense at the time because the readership was inevitably dominated by people who were online because they were interested in computers, or were connected through the universities. In twenty years that’s changed drastically: now it would be odd to expect readers to recognise wordplay on the Asking (ASCII) character set, or security on Eunuch’s (Unix) platforms. On the other hand, now that the web has become ubiquitous in so many lives, perhaps what should seem odd is that most people using it really do know next to nothing about how the internet works.

With that in mind, it’s worth reflecting on how prescient The Concuspidor & the Grand Wizard of Many Things was. The premise of the technology it describes is that users ask questions that all feed to the Grand Wizard of Many Things, who fields those requests by dipping into his Box of Answers and sending responses back. Could it be that the Grand Wizard of Many Things is indeed Google? Remember this was back before Google existed, when search engines still really cared about taxonomies, and long before the idea that people would commonly navigate the web by asking questions in the browser itself. Even fibre optics are not quite so far from the mirrors and pipes that make the Concuspidor’s “information sewer pipeway” work.

So three cheers for that prince of rakes and chancers the Concuspidor, who put Beholder online and who remains here twenty years later, long after more lavish or costly projects have arisen and faded away.