Miyamoto Musashi was probably the most famous swordsman in all of Japan, and he created the ni-to ryu, or two-swords, school of fighting. As readers of Fudebakudo know, there are several versions of the story of how this came about (the book mischievously contains two contradictory accounts), but one of the most enduring is that the secrets of this new, radical way of fighting were revealed to him by a mountain tengu.

Tengu is usually translated as "goblin," which of course loses something cultural in the translation (see this Wikipedia entry on the topic for more detail). But generally it is accepted that the tengu were reclusive mountain goblins with big noses who had unsurpassed and alien skills in swordmanship.

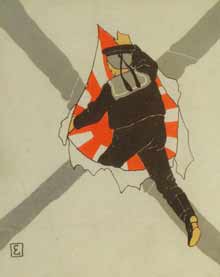

Tengu: Huge nose; bulgy round eyes; black, white, and red colouring; cartoony demeanour. Indisputable Western Fudebakudo influence.

The cheaty nature (fighting with two swords when everybody else was doing the decent thing following convention and using just the one, in the right hand), the big noses and — most subtle of all — the red and black colours that are frequently seen in contemporary woodcuts showing tengu, all point to the presence of European Fudebakudo. Rather than sacred goblins in mountain hideaways, might these not have been gaijin, Western devils teaching methods outside the box (or, as Fudebakudo scholars put it, "outside the lacquered box")? Could it be that, in this way, foreigners introduced underhand Fudebakudo tactics into hitherto honourable Japanese sword-fighting? They were reclusive because, as outsiders, they had no position in Japan's rigid social hierarchy. In fact, Japan actively rejected foreigners such as these when it adopted the sakoku policy of closing itself off from the world, which was instigated within Musashi's lifetime. It's possible that this was as a direct result of the samurai classes seeing (or suspecting) the influence such foreigners had had on him — he'd started beating them with these new strategies, after all.

Certainly it is known that Fudebakudo principles were at work in European fencing schools at the time (see this previous blog entry), and that a similar reintroduction of an Eastern military concept from the West had occurred just half a century earlier, when the Portugese began trading firearms with Japan's gunless rulers.

Of course, the truth is that we will probably never really know, because so few tengu survive today, and those that can be approached (such as the isolated captive specimens in the restricted-access area of Tokyo's Ueno Zoo) are invariably vague and elusive when questioned on the topic. So the reintroduction of Fudebakudo to Japan via European hideaways remains a controversial and perhaps taboo explanation of Musashi's brilliance and, in consequence, an overlooked influence on Japanese sword-fighting.

Anyway, years later our fine proofreader Judith (assisted by our US despatch ninja Eric) spotted this historic precedent from the

Anyway, years later our fine proofreader Judith (assisted by our US despatch ninja Eric) spotted this historic precedent from the